If you were a student in the Denver Public Schools between 2008 and 2019, you may not have realized it at the time, but you were likely benefiting from the most comprehensive and effective education reform initiative in the history of the United States. You were learning more than students in other comparable Colorado school districts, and you were more likely to graduate within four years than students from previous years. This held true regardless of your ethnicity and if you were part of a historically underserved population. Moreover, the improved learning outcomes you experienced during that period are destined to have a lasting impact on your life and almost certainly on your children’s lives as well.

If you were parent (or grandparent) of a Denver Public Schools (DPS) student during that time, you may remember that the DPS reforms sparked heated debate. On the one hand, parents enjoyed more choice in where their children attended school, while on the other they may have seen established neighborhood schools closing, new charter schools opening, and more pronounced turnover among teachers, principals, and other school staff. It may have been natural to wonder what good could come from so much upheaval.

It turns out quite a lot, according to the results of a landmark study by the Center for Education Policy Analysis at CU Denver.

The Proof is in the Data

Over the years, many of the arguments for and against the DPS reforms have been subjective, relying on limited, anecdotal evidence. Crucially missing was a broader, more data-driven analysis of the reform’s actual impact, which is where the Center for Education Policy Analysis (CEPA) in the School of Public Affairs (SPA), comes into the picture. Led by Parker Baxter, JD, Scholar in Residence at SPA and CEPA’s director (pictured below), a team of researchers embarked on a robust statistical analysis to determine whether Denver’s school reform strategy improved academic outcomes for students. What they found was striking.

According to the report, students enrolled in DPS between 2007-2018 received the equivalent of at least 9 months and as much as 14 months of additional schooling than students in comparative Colorado districts. Students enrolled during that entire period received an additional year to 1.5 years of additional learning. (Baxter, P., Nicotera, A., E. Fuller, J. Panzer, Ely, T., Teske, P. (2022). The System-Level Effects of Denver’s Portfolio District Strategy)

In other words, an 11th grader in 2019 would have learned as much as a 12th grader in 2007 learned, based on CEPA’s analysis of student test scores, specifically in the areas of English Language Arts and math achievement.

Students were also much more likely to graduate on time. Prior to 2008, only 43% of DPS students graduated in four years. By 2019, the four-year graduation rate had jumped to 71% of students. Such an improvement can have a substantial ripple effect on communities, creating more opportunities for students to pursue higher education and better paying careers.

Moreover, the CEPA study revealed that students from all demographic groups made improvements, which is especially significant given that DPS is one of the most diverse school districts in the state. “I was surprised to see the consistency of the results across the whole school system, even across special populations,” Baxter remarked. “We don’t really have other examples of education interventions that have this level of consistent, positive results at scale.”

The Three Levers of Reform

When the reforms were initiated in 2008, Denver was one of the lowest performing school districts in Colorado. In terms of test scores, DPS students ranked among the bottom 5% of students across the state. At that time, 25% of Denver’s school-aged children did not even attend public schools in Denver—their parents opting instead to send them to private schools, charter schools, or schools in other districts. “People forget how bad DPS schools were then,” said Paul Teske, Dean of the School of Public Affairs and a member of the CEPA research team (pictured below). “But during the period of reform, DPS made incredible progress,” he added.

The DPS reforms that took place from 2008 to 2019 were rooted in three principles: (1) offering more choice for families, (2) granting individual schools more autonomy, and (3) holding schools accountable for student outcomes. The CEPA report refers to these as “levers” that DPS activated simultaneously to drive system-wide improvements. According to Baxter, the DPS approach stressed that schools, educators, and families (not the central office) should have the authority and responsibility to determine how best to educate the city’s children.

For families, this meant more opportunity to send their children to the schools of their choice. Instead of being assigned a single option, families could select up to five, and an algorithm DPS employed would ensure that they got the highest choice possible.

For schools, the reforms meant greater control over their curricula, staffing, hours, and other details that in the previous era the central DPS system office managed. “This allowed different models to flourish and to be tried and judged based on their success or failure. If it works, do more of it; if it doesn’t, pull back,” Teske explained.

At the same time, schools were held more accountable for student progress. If students were falling behind, individual schools as well the district itself had more flexibility to take action, from changing teachers to shutting down low-performing schools entirely. Of course, closing schools is difficult and disruptive (as critics of the reforms are quick to point out), and a significant number of schools closed during this period owing to low performance. In these instances, DPS prioritized working with families to place their children in new and better schools.

Promoting Equity Through Funding

In addition to making these structural changes, DPS modified its funding model to one centered on the needs of students. Using a system that weighed factors such as income, special education, and English language learning, DPS provided schools with students who had the greatest needs more funding than schools with students who had fewer. “Under the reforms, funding was based on the composition of each school’s student body instead of an average across the system,” explained Baxter.

This may help explain why the positive results of the reforms were so consistent throughout the entire school system, even across special populations. “It speaks to the equity behind the reforms,” said Baxter. “You’re not seeing this level of success at the expense of someone else— the success was broad-based.”

Another testament to the improvements across the system was the dramatic increase in enrollment during the reform era, from just over 70,000 students on the heels of a decade of flat enrollment to more than 90,000 in 2018, which according to Baxter is almost unheard of for a large urban school district. The CEPA study established that Denver’s overall population growth accounted for some of that increase, but certainly not all, indicating that more and more families were finding public schools in Denver attractive.

The Pendulum Swings Again

Baxter describes Denver’s reforms as the most comprehensive effort to restructure the delivery of public education in the country, replacing a century-old model of hierarchical centralization. He and his team also characterize the reforms as the among most effective in size, scale, and duration, and the learning outcomes for students as unprecedented in American history.

Since 2018, however, the tide has turned as the composition of the elected DPS board has changed to include more members holding critical views of the reforms. “If DPS was so successful in those years, why are they taking a different approach now?” wondered Teske. “From a public policy perspective, I find this fascinating.” Teske went on to explain that the pendulum around education reform has swung nationwide, “But at the time Denver was the leading example of a district taking such a comprehensive approach,” he said.

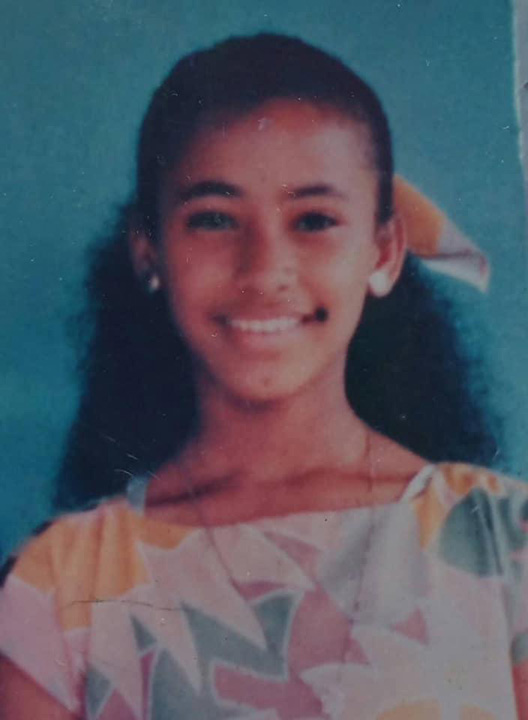

“The question of how to improve student learning at scale is one of the most significant challenges we face as a species in the U.S. and on the planet,” says Baxter reflecting on the broader implications DPS reforms. On a more personal level, Baxter can see the impact on individual students. “More than 2,000 additional students of color graduated from DPS and went on to college as a result of the reforms, and some of them are graduate students in my classes at SPA today,” he said. “We are only just beginning to see the fruits of that success.”

Research Powered by Philanthropy

CEPA’s study and subsequent report, The System-Level Effects of Denver’s Portfolio Strategy on Student Academic Outcomes, demonstrate the power of research fueled by philanthropy. The research was made possible by a grant from Arnold Ventures, which supports evidence-based solutions to society’s most pressing problems.

Having established a research base on the DPS reforms, the team at CEPA sees additional avenues to explore, including digging deeper to understand which facets of the reforms had the most impact. If you would like to support CEPA’s work in this area, please contact us at advancement@ucdenver.edu.

About CEPA

The Center for Education Policy Analysis works to improve public education by serving as a resource for education decision makers. The center works with schools, districts, state and federal agencies, nonprofits, and other universities to provide research and analysis on the issues facing public education. Its services include program design and evaluation, quantitative and qualitative research, policy and legal analysis, planning and facilitation, and expert staffing for public commissions and processes.

CEPA hosts the Summer Institute in Education Systems Leadership and Policy, a week-long interactive seminar in Denver designed for current and aspiring leaders and entrepreneurs working in public and private sector organizations engaged in education systems transformation and redesign. The curriculum provides an in-depth introduction to education systems leadership, politics, and policy, and offers participants an opportunity to explore the challenges and opportunities that come with redesigning how education is organized, governed, and