When Joey Morgan stepped foot on the CU Boulder campus in summer 2019, he felt like a 44-year-old stuck in a 24-year-old’s body.

Just one year before, Morgan had completed a tour of duty in Syria, fighting alongside the U.S. Army’s Kurdish allies and witnessing the lead-up to the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the Middle East.

“War was like a fever dream,” Morgan says.

Welcoming Veterans to Campus

Kristina Spaeth, an academic advisor at CU Boulder’s Veteran and Military Affairs (VMA) office, says it is common for veterans like Morgan to feel out of place when they return to school. Spaeth has spent the last decade working with veterans who fought in the Global War on Terror including the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The veterans enrolled in college utilizing the Post 9/11 GI Bill.

These are people who have sacrificed so much of themselves for the rest of us. The very least that we can do is to treat them right and do the right thing for them. Why not do the right thing?

– Kristina Spaeth, Academic Advisor

Her work serves the VMA’s overarching mission, which is to support student veterans and their dependents and provide them with information and assistance with their GI Bill benefits. Through her work at the VMA, Spaeth realized that veterans needed a bridge program to help them acclimate to academic and social life on campus before starting classes.

Kristina Spaeth, VMA academic advisor, discusses course selection with Connor Greenberg, a bridge program participant and CU Boulder student.

“These are people who have sacrificed so much of themselves for the rest of us,” Spaeth says. “The very least that we can do is to treat them right and do the right thing for them. At the time, creating the bridge program from nothing felt like the biggest challenge I’d ever encountered in my career, but it was like, ‘Why not do the right thing?’”

Working with Stewart Elliott, director of the VMA, Spaeth garnered the university’s support and launched the two-week summer bridge program in summer 2017 with 18 students.

Since then, the program has added a winter session and more than doubled in size, with 40 students in its 2021 summer cohort. The program provides intensive classes that enhance math, writing and research skills while also offering the opportunity for incoming veterans to network and form friendships.

Five years in, the bridge program is showing encouraging outcomes. Students who complete the program have a higher GPA and retention rate than those who do not.

Funding for Success

Private donor funding has helped the VMA grow over the years. Today, the office offers a range of services and support, including scholarships and student aid, career support, academic advising, tutoring, events and programming, a student ambassador program and more.

Student veterans study in the VMA student lounge.

“We are extremely fortunate to have significant financial support from foundations and private donors,” Elliott says. “This support has clearly transformed the CU Boulder VMA into a world class program supporting student veterans and veteran dependents who attend CU Boulder.”

As philanthropic support for the VMA has grown, so has support for the bridge program.

Spaeth says the program initially ran on a small budget from the university, but over time its success began to attract funding from private donors and organizations such as The Anschutz Foundation.

“I think our donors saw that we were doing the right thing for veterans,” Spaeth says.

Today, the bridge program is entirely donor funded. Philanthropic support enables the program to provide a $1,000 stipend to every student who completes the two-week program, up to 80 students each semester. In addition, donor support allows the program to compensate faculty and instructors who teach, speak on panels and connect with students.

Finding Purpose

Through the bridge program and other VMA programs, Morgan made friends and connected with civilians and veterans.

“At first, I didn’t know if I could effectively get along with civilians,” says Morgan, who is majoring in psychology. “But over time, I realized that there are people who want to know what we’ve been through in the service and that friends can be from anywhere, from different walks of life and any age from 25 to 75.”

That sense of belonging gave Morgan the confidence to forge ahead on an idea he had while visiting the grave of a friend’s father at Fort Logan National Cemetery in 2021.

“It was around the time that we were hearing about how the Taliban had taken over Afghanistan,” Morgan says. “While I was at the cemetery, the thought struck that we need a place that people will gravitate to, where they can reflect on what happened in the two decades, where veterans and civilians alike can mourn and remember the sacrifices of the survivors and the fallen – a place where we can meet in the middle, on common ground.”

After Morgan spoke to faculty involved with the bridge program about his idea, they connected him to the Global War on Terror Memorial Foundation and their plans for a war memorial on the National Mall in Washington D.C.

Joey Morgan at Old Main on the CU Boulder campus

Morgan is now serving as a veteran advisor for the memorial. He hopes to contribute to the memorial’s design, which currently includes bas-relief sculptures, photo galleries, plaques with the names of those who died in the war and a garden with flowers and plants from the Middle East such as tulips, jasmine and irises.

“The hope is that when someone visits who has been in these wars, they’ll feel a sense of recognition when they see the flowers,” Morgan says.

Spaeth says it keeps her motivated to see veterans like Morgan find a sense of purpose and place on campus.

“Some find lifelong friendships. They do club sports together and spend holidays together,” she says. “That’s why it’s so personally rewarding to do this work.”

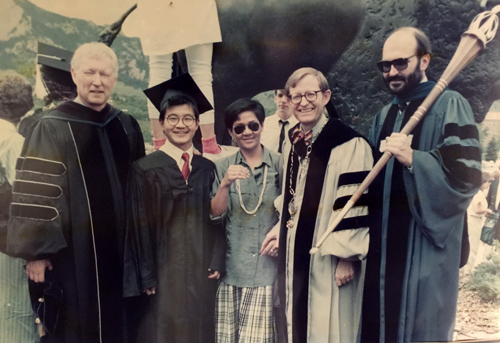

Tandean was an undergraduate business student from Indonesia and the first in his family to get a college education. His working-class parents, with only middle-school educations, helped pay for it by selling their house back in their village. He worked three jobs in Boulder—one of them washing pots and pans in Nichols Hall for $3.25 an hour—and only got haircuts twice a year. He borrowed money from his college roommate to pay his last tuition bill. But he felt lucky to have the American college experience, rooting for the Colorado Buffs football team and going to the popular college bar Tulagi with friends.

Tandean was an undergraduate business student from Indonesia and the first in his family to get a college education. His working-class parents, with only middle-school educations, helped pay for it by selling their house back in their village. He worked three jobs in Boulder—one of them washing pots and pans in Nichols Hall for $3.25 an hour—and only got haircuts twice a year. He borrowed money from his college roommate to pay his last tuition bill. But he felt lucky to have the American college experience, rooting for the Colorado Buffs football team and going to the popular college bar Tulagi with friends.